The Community Reinvestment Act: Unintended Consequences of Increased Regulation

The relaxation of lending standards is a significant component of the mortgage crisis. As it has evolved, the Community Reinvestment Act has gradually increased regulatory pressure on lending institutions, mandating a widespread loosening of lending standards. This has proven to be toxic after spreading throughout the market and contributing to the recent financial turmoil.

Background

Congress passed the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) in 1977 to reduce discriminatory credit practices against low-income neighborhood, known as “redlining.” The act requires the appropriate federally insured depository institutions to meet the credit needs of the local communities in which they are chartered, consistent with “safe and sound” operation. The vague wording of “safe and sound” was used by Congress to provide flexibility. As we will see, this flexibility has been crucial in allowing the act to evolve over time.

In the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) had “residential security maps” in which “unsafe” neighborhoods were outlined in red and mortgage capital was withheld from reaching inside. Redlining is now known as the practice of denying, or increasing the cost of services such as banking, insurance, access to jobs, etc. to low-income areas.

In 1977, most criticism stemmed from the fact that financial institutions would accept deposits from these low-income neighborhoods but they were unwilling to lend to or invest back in them, despite the fact that credit-worthy borrowers existed within.

However, as cited by Ben Bernanke in a speech he gave on the act in 2007, there are several other factors besides discrimination that may explain the issue of the unavailability of credit in low-income areas. These include: an underdeveloped secondary mortgage market; costs of gathering information in these areas were high; methods of gathering information in these areas was complicated; because of high regulations, banks were less competitive at the time. The CRA had the potential to induce banks to invest in building the knowledge and expertise needed to simultaneously lend to these low income areas.

In the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) had “residential security maps” in which “unsafe” neighborhoods were outlined in red and mortgage capital was withheld from reaching inside. Redlining is now known as the practice of denying, or increasing the cost of services such as banking, insurance, access to jobs, etc. to low-income areas.

In 1977, most criticism stemmed from the fact that financial institutions would accept deposits from these low-income neighborhoods but they were unwilling to lend to or invest back in them, despite the fact that credit-worthy borrowers existed within.

However, as cited by Ben Bernanke in a speech he gave on the act in 2007, there are several other factors besides discrimination that may explain the issue of the unavailability of credit in low-income areas. These include: an underdeveloped secondary mortgage market; costs of gathering information in these areas were high; methods of gathering information in these areas was complicated; because of high regulations, banks were less competitive at the time. The CRA had the potential to induce banks to invest in building the knowledge and expertise needed to simultaneously lend to these low income areas.

CRA Amendment Timeline

In the 1980s, concern over access to credit spurred the creation of the Financial Institution Reform and Recovery Act (FIRREA) in 1989. This act required public disclosure of institutions ratings and performance evaluation. The effect was an increase in advocacy groups and researchers involvement in performing analyses of banks records in meeting the credit needs of their communities.

In 1994, the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act eliminated restrictions of interstate banking in the US. This resulted in a rapid increase in mergers and acquisitions; along with this came an increase in advocacy groups’ protests. Banks now had even greater incentive to tune their strategies to expand CRA activity, this entailed further relaxation of their lending standards.

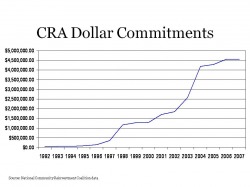

During the 1980s and 1990s, deregulation and increases in technology changed the structure of the banking system dynamically (notably the securitization of mortgages increased). By 1995, the Clinton Administration imposed new regulations, one of which required large institutions to face a three-pronged test based on performance in the areas of lending, investments, and services. This regulation placed the greatest emphasis on lending, and pushed “innovative” approaches for addressing community development. Effectiveness of the 1995 regulations was reviewed and the reforms were finalized in a new Amendment, which became official in 2005. In addition, CRA compliance tests for “small and intermediate small” banks were relaxed to generally just include lending tests. These commitments to further credit and housing were expanded and revised by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition's “CRA-Commitments” in 2007.

In 1994, the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act eliminated restrictions of interstate banking in the US. This resulted in a rapid increase in mergers and acquisitions; along with this came an increase in advocacy groups’ protests. Banks now had even greater incentive to tune their strategies to expand CRA activity, this entailed further relaxation of their lending standards.

During the 1980s and 1990s, deregulation and increases in technology changed the structure of the banking system dynamically (notably the securitization of mortgages increased). By 1995, the Clinton Administration imposed new regulations, one of which required large institutions to face a three-pronged test based on performance in the areas of lending, investments, and services. This regulation placed the greatest emphasis on lending, and pushed “innovative” approaches for addressing community development. Effectiveness of the 1995 regulations was reviewed and the reforms were finalized in a new Amendment, which became official in 2005. In addition, CRA compliance tests for “small and intermediate small” banks were relaxed to generally just include lending tests. These commitments to further credit and housing were expanded and revised by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition's “CRA-Commitments” in 2007.

Proof of Relaxation in Lending Standards

Source: National Community Reinvestment Coalition

CRA loans were generally low or no down payment or were made to borrowers with bad credit, all high risk attributes. Additional “innovative or flexible” underwriting standards included high debt to income ratios. These changes were implicitly required by regulators. From the National Community Reinvestment Coalition’s Website:

Underwriting Standards: Underwriting standards are the general guidelines used by lenders to approve or deny a loan based on the credit worthiness of the borrower and the value of the property. Traditional underwriting standards used by lenders can unfairly exclude low-income and minority applicants who may be credit-worthy. A number of CRA agreements contain provisions committing lenders to be more flexible in their application of underwriting standards.

Credit History: Many low-income and minority applicants often lack traditional credit histories or have a record of late payments that discourages lenders from approving a loan. CRA agreements include a more flexible approach to credit histories.

Employment History: Most lenders require borrowers to have between two and five years at the same job to qualify for a loan. This requirement often excludes low-income and minority applicants who change jobs frequently but nevertheless maintain a steady source of income. CRA agreements have included provisions to address this problem.

Income Source: In calculating an applicant’s ability to repay a loan, lenders traditionally have excluded calculating all sources of a low-income applicant’s income. CRA agreements have included provisions to broaden the type of income a lender will consider in evaluating the credit worthiness of a low income or minority applicant.

Obligation Ratios: Obligation ratios are used by lenders to calculate whether an applicant is able to afford a mortgage. Industry standards are generally set at 28 percent for housing expense-to-income and 36 percent for total debt-to-income. These standards in many instances are too low for low-income and minority individuals, who usually devote a higher proportion of income to housing expenses. Many CRA agreements have addressed this issue by committing lenders to use higher obligation ratios.

Because of the structure of the regulations, banks that were best at making CRA loans grew to be successful by making acquisitions and expanding operations, this increased exposure of their relaxed lending standards to the entire mortgage market.

Underwriting Standards: Underwriting standards are the general guidelines used by lenders to approve or deny a loan based on the credit worthiness of the borrower and the value of the property. Traditional underwriting standards used by lenders can unfairly exclude low-income and minority applicants who may be credit-worthy. A number of CRA agreements contain provisions committing lenders to be more flexible in their application of underwriting standards.

Credit History: Many low-income and minority applicants often lack traditional credit histories or have a record of late payments that discourages lenders from approving a loan. CRA agreements include a more flexible approach to credit histories.

Employment History: Most lenders require borrowers to have between two and five years at the same job to qualify for a loan. This requirement often excludes low-income and minority applicants who change jobs frequently but nevertheless maintain a steady source of income. CRA agreements have included provisions to address this problem.

Income Source: In calculating an applicant’s ability to repay a loan, lenders traditionally have excluded calculating all sources of a low-income applicant’s income. CRA agreements have included provisions to broaden the type of income a lender will consider in evaluating the credit worthiness of a low income or minority applicant.

Obligation Ratios: Obligation ratios are used by lenders to calculate whether an applicant is able to afford a mortgage. Industry standards are generally set at 28 percent for housing expense-to-income and 36 percent for total debt-to-income. These standards in many instances are too low for low-income and minority individuals, who usually devote a higher proportion of income to housing expenses. Many CRA agreements have addressed this issue by committing lenders to use higher obligation ratios.

Because of the structure of the regulations, banks that were best at making CRA loans grew to be successful by making acquisitions and expanding operations, this increased exposure of their relaxed lending standards to the entire mortgage market.

Fannie and Freddie and the HUD

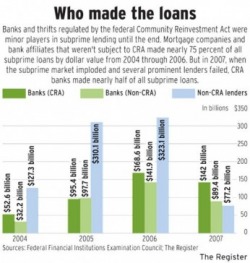

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, The Register

“Fannie and Freddie went from being the watchdogs of credit standards and thoughtful innovators to the leaders in default prone loans and poorly designed products. They introduced mortgages which encouraged and extended the housing bubble, trapped millions of people in loans that they knew were unsustainable, and destroyed the equity savings of tens of millions of Americans.” -Edward Pinto

The Department of Housing and Urban Development HUD's affordable housing goals required 55% of the loans they purchase to be affordable housing loans, 28% of which were required to be loans made to low and very low-income borrowers. Arguably, after their accounting scandals in '03 and '04, they were afraid of facing tighter regulation from Congress and used CRA lending as a means to avoid this.To reiterate, it was not the losses from actual CRA loans that drove the housing crisis, but the relaxed lending standards that they required which spread throughout the housing market.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development HUD's affordable housing goals required 55% of the loans they purchase to be affordable housing loans, 28% of which were required to be loans made to low and very low-income borrowers. Arguably, after their accounting scandals in '03 and '04, they were afraid of facing tighter regulation from Congress and used CRA lending as a means to avoid this.To reiterate, it was not the losses from actual CRA loans that drove the housing crisis, but the relaxed lending standards that they required which spread throughout the housing market.