What is the Glass-Steagall Act?

The Glass-Steagall Act was created in 1933 during the aftermath of the Great Depression. The "riskiness" of investment banking activities became the scapegoat for the financial crisis, and thus the government felt stronger regulation could help to prevent another recession from occuring. The Glass-Steagall Act banned commercial banks from underwriting securities, forcing commercial banks and investment banks to separate. By separating the two types of banks, commercial banks were made to be less risky ("The Long Demise of Glass-Steagall").

Changes to Glass-Steagall: Gradual Deregulation

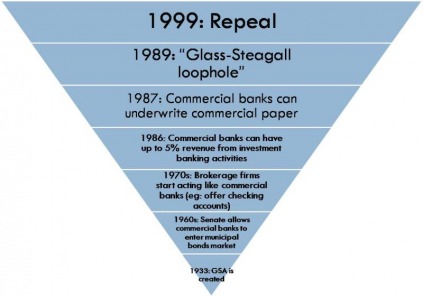

The Glass-Steagall Act was slowly loosened in the last 50 years of the 20th century as commercial banks felt they were struggling to compete with investment banks. The first major change occurred in the 1960s when commercial banks lobbied the U.S. Senate to allow them to enter the municipal bonds market, which they successfully achieved. Commercial banks began to feel really threatened in the 1970s when brokerage firms starting invading on commercial banking territory when they began offering money, market accounts that pay interest, check-writing, and credit/debit cards. By 1986, the Federal Reserve Board loosened Glass-Steagall by allowing banks to have 5% revenues from investment banking activities.

Deregulation through the expansion of commercial banking activities really began to progress in the late 1980s on through the late 1990s. In 1987, commercial banks were allowed to deal in the commercial paper, municipal bonds, and mortgage-backed securities markets. Citigroup backed this amendment to Glass-Steagall, saying the Act should be loosened because of the effectiveness of the SEC, more knowledgeable investors, and “very sophisticated” rating agencies. Federal Reserve Board chairman at the time, Paul Volcker, feared that lenders would recklessly lower loan standards in pursuit of higher revenues. Later in 1987, Alan Greenspan became Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Greenspan publically says that he is in favor of deregulation in order for U.S. banks to be more competitive with big foreign banks.

In 1989, major U.S. banking entities, like J.P. Morgan, Chase Manhattan, Bankers Trust, and Citicorp, are allowed into the “Glass-Steagall loophole”, which allowed commercial banks to deal in debt and equity securities. Within the same year, revenue from investment banking activities was extended from 5% to 10%. This was later extended to 25% in 1996. The late 1990s proved to be the demise of Glass-Steagall when the Federal Reserve Board argues that the risk of underwriting had proven to be “manageable” and banks were allowed to acquire securities firms. In 1999, after 12 attempts in 25 years, Glass-Steagall was officially repealed by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act ("The Long Demise of Glass-Steagall").

Deregulation through the expansion of commercial banking activities really began to progress in the late 1980s on through the late 1990s. In 1987, commercial banks were allowed to deal in the commercial paper, municipal bonds, and mortgage-backed securities markets. Citigroup backed this amendment to Glass-Steagall, saying the Act should be loosened because of the effectiveness of the SEC, more knowledgeable investors, and “very sophisticated” rating agencies. Federal Reserve Board chairman at the time, Paul Volcker, feared that lenders would recklessly lower loan standards in pursuit of higher revenues. Later in 1987, Alan Greenspan became Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Greenspan publically says that he is in favor of deregulation in order for U.S. banks to be more competitive with big foreign banks.

In 1989, major U.S. banking entities, like J.P. Morgan, Chase Manhattan, Bankers Trust, and Citicorp, are allowed into the “Glass-Steagall loophole”, which allowed commercial banks to deal in debt and equity securities. Within the same year, revenue from investment banking activities was extended from 5% to 10%. This was later extended to 25% in 1996. The late 1990s proved to be the demise of Glass-Steagall when the Federal Reserve Board argues that the risk of underwriting had proven to be “manageable” and banks were allowed to acquire securities firms. In 1999, after 12 attempts in 25 years, Glass-Steagall was officially repealed by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act ("The Long Demise of Glass-Steagall").

Reasons for Repeal

There were many different arguments for the repeal of Glass-Steagall. Firstly, the act was created to separate commercial banking activities from investment banking activities. By the late 1990s, this had been completely evaded, thus there was no real purpose for the act. Secondly, according to Alan Greenspan and his supporters, the Act hurt U.S. commercial and investment bank’s competitiveness. Foreign banks were bigger and less regulated, so they were thought to be more competitive at the time. Thirdly, separating commercial and investment banks imposed significant financial costs to firms. Many supporters of this theory thought competition between the two types of banks hurt their revenues. This was later proved false. Fourthly, total prohibition of investment banking activities in commercial banking was impractical from the very beginning. Lastly, some academics proved that securities activities in commercial banking actually had nothing to do with the great depression. This is still highly debated, thus weakening the necessity of the Act. Ultimately, the Repeal was meant to help American banks grow larger and be more competitive around the world (Barth).

Why was the Repeal Controversial?

Since the Glass-Steagall Repeal, banks have been creating wealth by packaging individual loans into bundles and selling them for a fee. These bundles included pieces of mortgage-backed securities, asset-backed securities, and collateralized debt obligations. Today, the main concern with these bundles is that no one really knows what they are worth, thus no one wants them on their balance sheet. Another issue surrounding the Repeal of Glass-Steagall was the formation of mega banks, like CitiGroup. These mega banks allowed deposits and loans to be turned into debt or capital to fund the sale of the bundles discussed in the previous paragraph. This added to the risk because there was a gamble involved with whether that asset would perform well or not. Mega banks did this on a large scale and banks that thought they were “too big to fail” actually did fail because of this speculation game (Barth, Kitch).

What does the Future Hold for Glass-Steagall?

In 2009, Congress began to discuss regulation in the banking industry and how to prevent another economic crisis of this nature from occurring again. Two sides emerged. Senator John McCain, Republican Senator of Arizona, and Maria Cantwell, Democratic Senator of Washington, joined forces in a campaign to bring Glass-Steagall back into legislation. Under this plan, commercial banks would be forced to split from their lucrative, yet risky investment banking operations. If this happened, for example, Bank of America would have to sell off virtually all of Merrill Lynch.Other the other side of the argument is the Volcker Rule, which is backed by President Obama. This plan would allow mega banks to stay intact and would focus mainly on the regulation of hedge funds and private equity funds. If this was implemented, for example, Bank of America would be able to keep Merrill Lynch’s brokerage service as part of their bank (Sanati). With new financial regulations under way, this debate will have a heavy impact on the future of banking - regardless of which side wins.